Are you worried that your child is developing an eating disorder? Maybe you’ve noticed body image concerns, skipping meals, and diet culture creeping into your home. As a loving parent, you want to help, but you’re not exactly sure you know how. You’re also curious if there’s a difference between disordered eating versus an eating disorder—and if that even matters.

A warm welcome to you! I am Marissa, Family Nutrition Expert & Corporate Wellness Dietitian, and mom to two girls. I help my clients find peace, health, and balance with their eating behaviors.

In this article, I’ll walk you through the warning signs you need to be on the lookout for so that you can determine if your child is struggling in their relationship with food. By the end, you’ll have a better understanding of what next steps to take.

Let’s dive in with an overview of the difference between disordered eating and an eating disorder.

Listen to this article:

The differences between eating disorders vs disordered eating

It’s not exactly straightforward—because there is a lot of overlap.

Plus, it doesn’t help that these terms are essentially mirror versions of one another.

But they are different.

Put simply, eating disorders are diagnosable—and disordered eating is not.

Unlike disordered eating, eating disorders are considered mental illnesses that physicians and therapists diagnose using a guidebook called, “The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).”

The DSM-5 manual allows providers to be able to easily differentiate among occasional unhealthy eating behaviors, disordered eating habits, and a diagnosable eating disorder.

So, let’s get down to the nitty gritty!

What are common pediatric eating disorders?

Did you know that there are actually several different eating disorders that are common with kids? Here is a brief overview of what some children are experiencing (1).

- Anorexia Nervosa (AN): AN involves a distorted body image and fear of gaining weight, along with extreme restrictive eating, which can lead to significant weight loss.

- Bulimia Nervosa (BN): BN includes episodes of excessive eating or bingeing followed by compensatory behaviors such as purging (vomiting/laxative use), fasting, or compulsive exercise.

- Binge Eating Disorder (BED): like BN, BED involves recurring episodes of excessive bingeing but without following it up with compensatory behaviors, leading to feelings of a loss of control.

- Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID): ARFID is having very limited food preferences, accompanied by an avoidance of certain qualities in food, such as textures, smells, and colors, which can lead to inadequate nutrition.

- Pica Disorder: Pica is the consumption of non-nutritive or non-food substances, such as dirt, soil, paper, chalk, or hair, which lasts for at least one month.

- Rumination Disorder: Rumination is when food is re-chewed, re-swallowed, spit out or regurgitated repeatedly.

- Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder (OSFED): OSFED includes significant abnormal eating behaviors that don’t necessarily fit the diagnostic criteria for any one specific eating disorder, but that are more severe than disordered eating.

It should be noted that orthorexia nervosa (ON) involves an unhealthy fixation on healthy eating. However, there’s still debate about if this condition should be classified as an eating disorder or as an obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (2).

To compare eating disorders with disordered eating, we’ll concentrate on the following four disorders that we included in this list: AN, BN, BED, and OSFED.

How is disordered eating different?

Disordered eating is an “umbrella term” for when someone has one or more “disordered” beliefs or behaviors, but they don’t exactly match with one of the diagnosable conditions that we discussed earlier (3).

As with eating disorders, those with disordered eating can have unhealthy beliefs about their body, eating and food. This is also accompanied by behaviors that are neither balanced nor healthy.

Some disordered eating behaviors might also include some of the same behaviors on the criteria list for eating disorders, but not “enough” to warrant a diagnosis in the DSM-5.

For instance, you might observe your child eating in secrecy or heading to the bathroom after meals, possibly to purge; however, he might not be engaging in these behaviors “regularly enough” to meet the criteria for BN.

Here’s the thing, not meeting a specific DSM-5 diagnosis doesn’t make disordered eating any less serious.

As you can see, the problem is still there, but the difference lies in the severity and frequency, as well as any mental and physical impacts to your child’s well-being.

And as a dietitian, I also know that disordered eating – if left untreated – can evolve into a full-blown eating disorder. It’s never too early to help your child cultivate a healthy relationship with food and their body.

When can disordered eating cross over into an eating disorder?

Like most things, there are nuances here.

Eating disorders and disordered eating share behaviors and attitudes about food and body image, but they can often differ in severity and impact on your child’s life.

Let’s start with where they overlap.

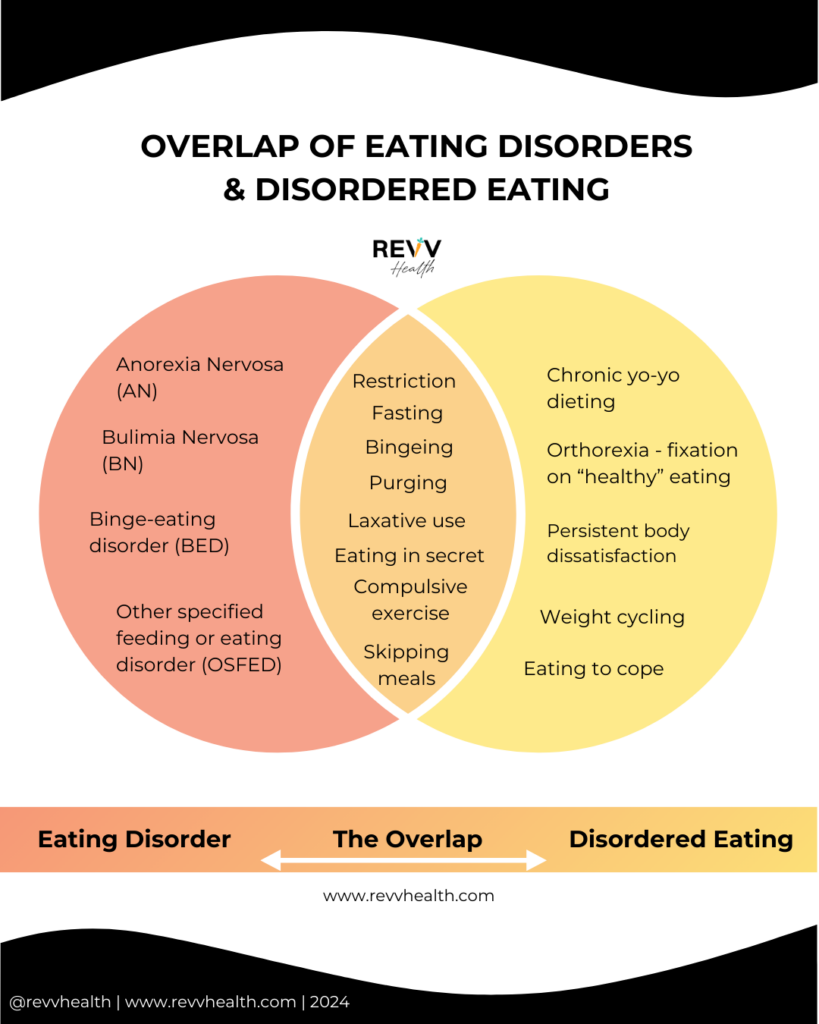

You might be a visual learner. If so, it’s helpful to look at the overlap with a Venn diagram:

As you can see, the overlap includes behaviors where both eating disorders and disordered eating may involve the following:

- Restriction: severely limiting the amount and types of food consumed, which might lead to inadequate nutrient intake.

- Fasting: in the context of eating behavior, fasting is voluntarily abstaining from food or drink for a specific period for weight-related reasons.

- Bingeing: the uncontrollable consumption of large amounts of food in a short period of time.

- Purging: a compensatory behavior to eliminate consumed calories, such as vomiting or using laxatives, following a binge.

- Laxative use: the misuse of a stool softener or stimulant to attempt to remove calories or weight, risking adverse health effects.

- Eating in secret: consuming food in isolation, often due to shame or guilt associated with the act of eating.

- Compulsive exercise: an excessive pattern of physical activity to control weight.

- Skipping meals: the intentional omission of regular meals, disrupting normal eating patterns.

Both eating disorders and disordered eating include a preoccupation with food, thoughts about eating, and guilt related to food choices.

While disordered eating isn’t officially diagnosed, if left unaddressed, it can progress to meet all the criteria required for an official eating disorder diagnosis.

What can happen if my child has disordered eating?

Disordered eating and eating disorders each carry significant risks to your child’s health.

Physical risks:

- Eating disorders: children with eating disorders often have severe physical health issues. These issues can impact many organ systems, such as the heart, skeletal, digestive, and other organs like the skin, to name a few. Nutritional deficiencies are also common due to sustained and extreme behaviors like bingeing, purging, or severe restriction.

- Disordered eating: can result in your child having similar physical health concerns as listed above, but they tend to be less severe or chronic compared to eating disorders.

Mental health risks:

- Eating disorders: children with eating disorders also have a risk of a severe mental health condition. This includes clinical depression, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), as well as the risk of suicidal thoughts or behaviors (4).

- Disordered eating: can lead to stress, guilt, and negative body image, but the impact on mental health tends to be less severe and chronic compared to diagnosed eating disorders.

The key difference often lies in the intensity, duration, and severity of behaviors.

Eating disorders typically involve more extreme and persistent behaviors, leading to more severe physical and mental health implications compared to disordered eating.

Nonetheless, both warrant attention and medical support for complete recovery and improved health.

How do I know if my child has an eating disorder or disordered eating?

Firstly, you will not be able to determine this on your own!

You will want to reach out to your child’s pediatrician, therapist, or psychiatrist.

While any one of the following healthcare professionals can diagnose (or rule out) an eating disorder, typically more than one healthcare professional is involved to ensure a thorough evaluation of your child’s physical and mental health.

These professionals may include:

- Pediatrician: physicians can assess physical health, conduct medical examinations, and order relevant tests to rule out any underlying health issues related to the eating disorder.

- Psychiatrists: mental health professionals specializing in psychiatry may contribute to the diagnostic process, particularly in assessing the psychological aspects of an eating disorder.

- Psychologists: clinical psychologists are trained to evaluate and treat mental health conditions, including eating disorders. They may conduct psychological assessments and provide therapy.

- Licensed mental health counselors or therapists: these professionals can also be involved in assessing and treating individuals with eating disorders, providing therapeutic interventions and support.

Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (RDNs) specializing in eating disorders can assess nutritional status and dietary patterns; however, we cannot officially diagnose an eating disorder.

That said, as a dietitian who specializes in eating disorders and disordered eating, we are an integral part of your family’s full treatment approach.

What treatment approach is effective for eating disorders and disordered eating?

There are many approaches, but the main rule of thumb is to establish care with a “trifecta team.”

This trifecta is a multidisciplinary team that consists of three primary specialists who collaborate to provide comprehensive care.

This team should include:

- A therapist or psychologist: to address the psychological aspects, such as body image, self-esteem, and emotional triggers associated with the eating disorder or disordered eating.

- A registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN): to offer guidance on nutrition and meal planning, assisting in establishing better eating patterns, addressing nutritional deficiencies, and managing any physical complications related to the eating disorder or disordered eating.

- Doctor or psychiatrist: to monitor your child’s physical health, vitals, bloodwork, and any medical complications arising from the eating disorder or disordered eating. They also may prescribe medication for co-occurring conditions like anxiety or depression.

How do I spot early warning signs?

Recognizing problematic eating behaviors, such as disordered eating patterns, allows you to seek help early.

Consider consulting a medical provider if you observe the following:

- Your child is frequently skipping meals

- Her menstrual cycle was regular, but stopped

- Unusual weight changes (gain or loss)

- Concern about body weight or image

- Excessive exercise beyond regular activity levels

- Frequent restroom visits after meals

- Eating alone in their bedroom

- Heightened focus on food quantity or timing of meals

- Sudden reluctance to eat with the family

- Self-imposed rules with eating

- A fixation on “only eating healthy foods”

With early treatment, you may be able to help prevent your child’s eating behaviors from becoming pathological.

What can I do as a loving parent?

You’re here now, which means you really care.

Unlearning common diet culture practices is a great start. You can help normalize the idea that “all foods can fit” into your child’s diet.

Sometimes, we might not realize how our own upbringing about food plays a major role in how we shape our children’s beliefs.

Some self-reflections to consider:

- Am I a competent eater? Evaluate your own relationship with food and eating habits.

- What is our family food environment like? Calm, tense, restrictive, permissive?

- Am I talking about my body weight around my kids? Reflect on the type of comments you might be making about body weight in conversations with your children.

- Am I creating calm or tense eating environments for my family? Even subtle pressure or nudging to “eat more or less” can create control issues at the table.

- Do I have a history of untreated disordered eating? Now might be a great time to start seeking help for yourself!

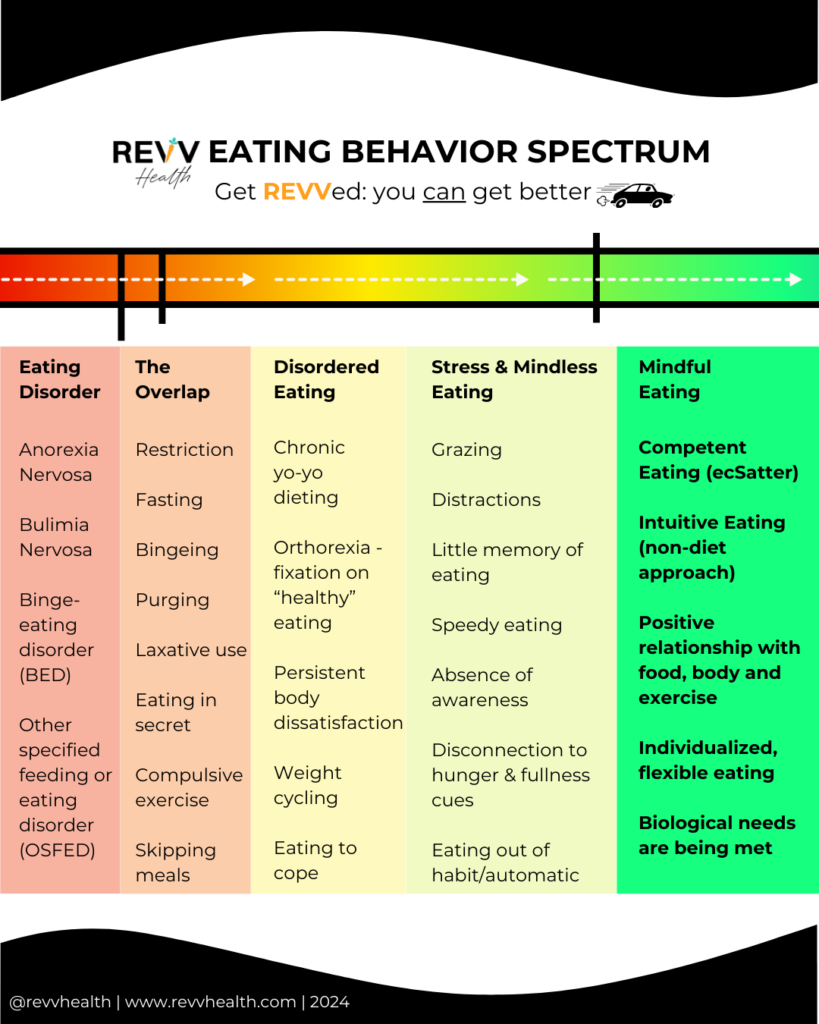

- Where am I personally on the eating behavior spectrum? Take a look at the graphic below to see what resonates the most.

If you notice you’re not “in the green,” now can be a wonderful time to take proactive steps to seek help.

How I can help

Eating disorders and disordered eating have a lot in common, and now you’re plugged into some of the key differences.

No matter what: they’re not something to be ignored. Your child unfortunately won’t just outgrow them and without treatment, they’re likely to get worse.

Are you ready for a friendly chat with someone who understands?

I’d like to help you get a step closer to healing. As a registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) specializing in disordered eating prevention and treatment, I am dedicated to supporting overwhelmed parents and their children on the path to full recovery.

The hardest step is often the first one. I get it. It’s why I offer a casual, no-obligation, free 20-minute discovery call. During our conversation, I’ll listen to your story, answer your questions and provide initial guidance.

Following our call, you’ll have a clear roadmap for the next steps in getting your child appropriate support.

You don’t have to shoulder this worry alone. I am here to help: [Book your free 20-minute call here]

Your blog is always a highlight of my day

Keep up the fantastic work!

Wow, this blogger is seriously impressive!

Your blog post was really enjoyable to read, and I appreciate the effort you put into creating such great content. Keep up the great work!

Your blog post was really enjoyable to read, and I appreciate the effort you put into creating such great content. Keep up the great work!

Looking forward to your next post. Keep up the good work!